A personal story about narrative and Narrative Warfare in a combat zone

Why the US and NATO continue to lose badly, on the cognitive battlefield.

Dear TAT readers,

This first of two TAT works today, is actually the introduction to a book that I co-wrote with the founder and CEO of our think tank, Narrative Strategies, Ajit Maan, PhD. This is my personal story, during one of my yearly Afghan deployments over five straight years. I share this story because ours and NATO’s security communities, have been losing at influence, to adversaries like Russia, China and their co-evil empires, for four decades. We, like NATO, are what I call, “impotent on the cognitive battlefield.” The sad truth is, that we continue to go down rabbit holes towards nonsense concepts, and have a total lack of imagination and leadership.

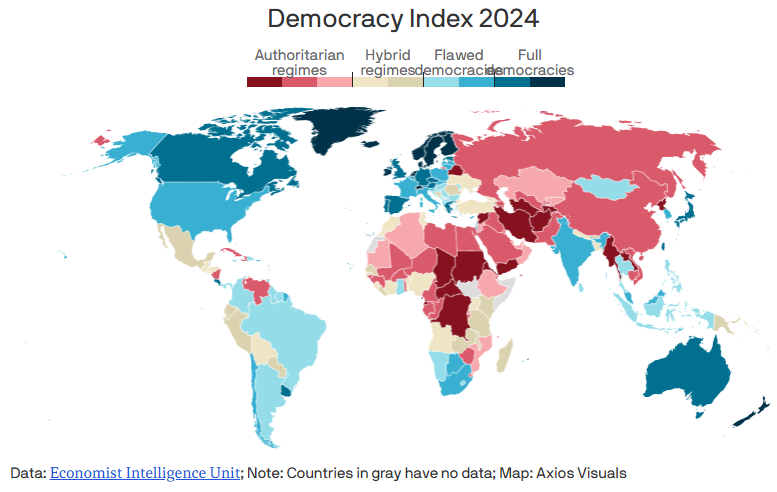

In the past forty years, global democracy has shrunk precipitously and now, under this pro-Putin administration, we are actually allied with Russia and others in his orbit. Our constitutional republic is under threat, around the clock and the entire professional influence community, is still holding conferences and wasting money on the utter nonsense with new names, that we have wasted billions on over those four losing decades.

Today, I thought that readers, may very well understand better than these overpaid and dramatically under-performing “experts” and their nepotistic contracting firms that are also overpaid. All that we get back, for all of those billions, is more failure. The community at large, falsely believes that technology is the answer. While that technology could possibly play important roles in Narrative Warfare, it is quite far from being the primary tool and not at all, so long as they pursue 1990s concepts and ridiculous boondoggles.

It is my former professional community that is more to blame for our current perch on the cliff of failure as a republic, than any other profession. I have nearly written about this topic, to the point I am wearing out my fingerprints on this critical vulnerability in our national security, but to no avail. The nepotistic contractors, alleged experts and their nepotistic contracting officers, are just like their military and civilian counterparts, blinded by four straight decades of BS and that give us nothing in return.

We cannot remain a republic unless we learn how to manage what is professionally called, “malign influence,” from both domestic and foreign adversaries. As we learned from the full Russia Report and a great deal more, the GOP in the Trump era has become a domestic tool of Russian influence campaigns, both wittingly and unwittingly. Our backs are now against the wall. Will my former community finally get off of their hind quarters and learn, or will they simply continue pontificating about what they will do, but never get around to?

Food for thought for your weekend,

Paul

The young Pashtun Taliban fighter glared defiantly, at the old American soldier in civilian clothes, sitting quietly and calmly erect in front of him. His glare even penetrated the smoke, from the interpreter’s perpetually lit cigarette. That smoke filled the dusty plywood room used for interrogating recently captured Taliban and other extremist fighters, on a small base in far eastern Afghanistan during the winter of 2010-2011. The young fighter had no idea that he was about to be my guinea pig, in a new approach that would trouble him deeply, and elicit in him instinctive involuntary responses. The new approach was simply telling the young fighter a story. The effectiveness of this unique story, surprised me nearly as much as it troubled him.

In the months before this latest deployment, I had stumbled onto this young Taliban’s greatest vulnerability. In my time between yearly deployments, I had armed myself with the knowledge of who he was, not just his name and cursory information but his personal cultural identity. In the hour or so I spent with him, my new tactic was to spin a special kind of a story called a narrative, laced with cultural identity triggers both in terms of content and structure. In other words, it was not just the topic of the narrative that was operative, but also the way I told it. I was telling the narrative in a manner, consistent with the way rural Pashtuns, with my “greybeard status, would express themselves to another within their local tribal community.

I began speaking slowly in a low voice, explaining that if the US Army allowed it, I would have a grey beard, a cultural attribute suggesting he was honor-bound to respectfully hear what I had to say. The grey beard indicated that I was an elder. His initial glare gave way to uncertainty as he leaned towards me to hear my quiet but confident words, a subtle sign of deference to Elders. With respect for the “grey beard” established, his identity as a Pashtun had been triggered and though he did not know it consciously, his planned resistance strategy had already begun to unravel.

Over the course of the interview, I avoided asking direct questions but wove as many relevant tenants of Pashtunwali, the honor-based tribal code, into my story. This approach of who I was and why, based on Pashtunwali, his behavior was shaming his family, clan, and village. Instead of focusing exclusively on facts, I explained the meaning of the facts as a rural, Ghilzai Federation Pashtun, would interpret them. The facts concerned his actions, but the meaning of the facts, implied shame.

My story was about how I, as an American, had learned about Pashtunwali and was now interpreting the behavior of local fighters through a new lens, including his. I carefully told him that I had not only studied, but had sat drinking tea with local elders who had honed my newfound knowledge. I did not outright condemn or shame him but suggested, that based on my knowledge of his actions, “wouldn’t local elders, very likely interpret his behavior as shameful for his family, clan and village”? In honor-based societies, the yin vs. yang-like relationship between honor and shame is powerful.

My story was not merely “talking at” him but included carefully solicited interactions from the young man. My story along with his interaction meandered across many topics such as; where he stood in the patrilineal hierarchy of his family, and the traits his father displayed in respect to the various honor-based requirements of Pashtunwali. We discussed his male siblings, cousins and how and to what extent they followed the tenets of Pashtunwali. Like any decent trial lawyer, I did not ask any questions that I already did not know the answer to. Based on his answers, I asked him to compare his father’s honorable traits with the traits displayed by his Taliban leaders.

I used his own words to paint a picture of honorable behavior. In the end, I let him see that it was he, not I that had condemned his actions with local Taliban groups. He, through his own words and interpretation of Pashtunwali demonstrated the shame he had brought on his family and his tribal affiliations. With every self-acknowledgment of his shame his head sank lower and his shoulders slumped similarly.

The final straw came with a simple question; “Would you prefer that I travel to your village and ask the elders personally for their opinion about whether his activities with the local Taliban brought shame and dishonor to his village and family”? The young Taliban, now leaned in towards me and began to slowly rock, drawing his arms tightly to his chest. His moist eyes widened. I held his gaze with a firm but open expression allowing the lessons of my story to fully sink in. When the weight of the millennia old tribal code weighing on his conscience registered fully, he broke. The knees he had been resting on were drawn to his chest he began to cry and then sob.

In the end, the young fighter had begged to not be exposed as dishonorable. I had not lied. I had not threatened him nor employed any harsh tactics. I had merely told him a story, all true but shaped with meaning as a rural, greybeard Pashtun would shape it.

The young man was not broken psychologically but his bond with the narratives of his Taliban ideology had been, at least for the time being. My careful triggering of his identification with tribal honor, had displaced the narrative of his Taliban leaders.

It would be another four years from that cold winter night in eastern Afghanistan, before I learned that narrative was not just story-telling but the heart of the art and science, of influence. In late 2015 as I prepared to retire from the US Army, I was pondering “what comes next?” I stumbled onto a small group of academics and former military professionals who had similar experiences, and the academic chops, to verify my belief that I had won my very first battle, in Narrative Warfare, the specialty of our think tank, Narrative Strategies.

The group was led by a preeminent scholar in the field of narrative, Dr. Ajit Maan. She literally wrote the book on the role narrative identity plays in triggering behavior. Through our discussions I realized that the story I had told to the young Taliban fighter, four years earlier and in a variety of fashions in the yearly deployments afterwards, actually had a name. It was called narrative.

Over the ensuing months, our little group of like-minded professionals began to fill the critical gap in how the US goes about non-kinetic influence. We put narrative directly at the core of influence campaigns. Since then, we have been sharing our decades of knowledge and experience with national security strategists and operators, offering mentoring and hands-on assistance to those attempting to address our most serious threats.

An overwhelming number of conflicts and instability now defining the international security environment are recognized across the board as “conflict, beneath the threshold of war.” Simply put, this means influence is now the name of the game. It is our opinion, that all campaigns of influence are, Narrative Warfare.

How can the US and allies compete effectively in such contests if we do not understand what narrative is and how it predictably triggers behavior, when understood well and managed by true operators? Tragically, DoD and most of the national security community, refused to learn these lessons and although they now claim to be engaged in Narrative Warfare, they are deluding themselves due to decades of nepotism and alleged, “experts” using the word narrative in their contract proposals to acquire lucrative contracts that they can never perform. Clearly, many of our adversaries understand narrative as superficially as our own national security community. Extremists understand, Russia certainly understands just enough to perpetually win, against us and our allies, but mostly because we and NATO do not campaign, never ask operators for guidance and mostly wield technology that is at best, a pin-prick to our adversaries.

The question is, “when will we as a security community understand, this powerful tool of persuasion and employ it in pursuit of our national security goals? “It certainly will not be via the newest DoD boondoggle at Ole Miss, where we have heavily invested in something falsely promoted and the “National Center for Narrative Intelligence.” They know nothing of Narrative Warfare and are relatively devoid of even understanding narrative.

The bottom line is that we cannot compete with adversaries like Russia, China and India in influence operations, because DoD does not train operators nor narrative from those who understand it.

Narrative is not just relevant to Pashtuns. We all have identities which also means that we all have our own, personal narratives. This is what Sun Tzu was talking about with his quote about “knowing yourself and knowing your enemy.” Narrative is both art and science and when used ethically, is a powerful and requisite tool of influence. It is in fact, the core of all human influence.

What follows, in this first of its kind book, is an introduction to this powerful yet currently misunderstood critical field.

Paul Cobaugh

San Antonio, Texas

June, 21st, 2018

Additional background reading regarding Influence, from a national security perspective.