Replaying this essay regarding, how that DHS, the FBI and the National Security Community, are still failing us at a critical period of our history.

Violent extremism is a plague on our house.

Happy Sunday TAT readers,

Today, as we experience deep rifts based on competing narratives about college protests, the war in Ukraine, the fake GOP narratives about the border and inflation, it’s time to get a handle on who is responsible for protecting us from propaganda, mis/ disinformation and false narratives.

While that it falls primarily to DHS and the FBI to protect the homeland, they are simply part of a far worse and potentially mortal approach to defending our republic and by extension, global democracy.

The US national security community is and has for generations, utterly failed at influence operations, with very few, niche exceptions. They continue to listen to the same failed experts that are driving policy and handing out contracts to those same alleged experts that have failed us for decades.

They shoulder the lion’s share of the blame for Russian influence operations that had such a negative impact, on our 2016 election. In the eight years since, not one thing of substance makes us safer from domestic and foreign influence operations. Some of these operations, such as the cooperation between MAGA and Russia, have become far more dangerous threats due to their inaction and poor focus on what matters.

I am replaying this today because there is too much at stake, to not speak out often and pointedly.

My best for what is left of everyone’s weekend,

Paul

Below is the article originally titled; Hey there DHS and FBI, this is for you

Happy Monday TAT readers,

Today is something very different. As I am preparing for some upcoming work on the plague of domestic extremism and violent extremism, I dug out something I wrote back in 2017. I had been invited to Germany to participate in CVE work or better known as Countering Violent Extremism. One of the outputs of the conference was to be a book discussing the topics of the conference. I was honored to provide the first chapter in the book with a paper titled, “CVE without Narrative, “A book without a story.” At this point, I had only been retired from the Army for a little over a year.

The main effort in my military CT/ Counterterrorism work, had been Islamic violent extremism. My earlier CVE work for the US Special Operations Command had given me deep experience in the dynamics of extremism, violent extremism and more than enough first-hand, combat zone experiences, which had been my laboratory of sorts, testing my theories.

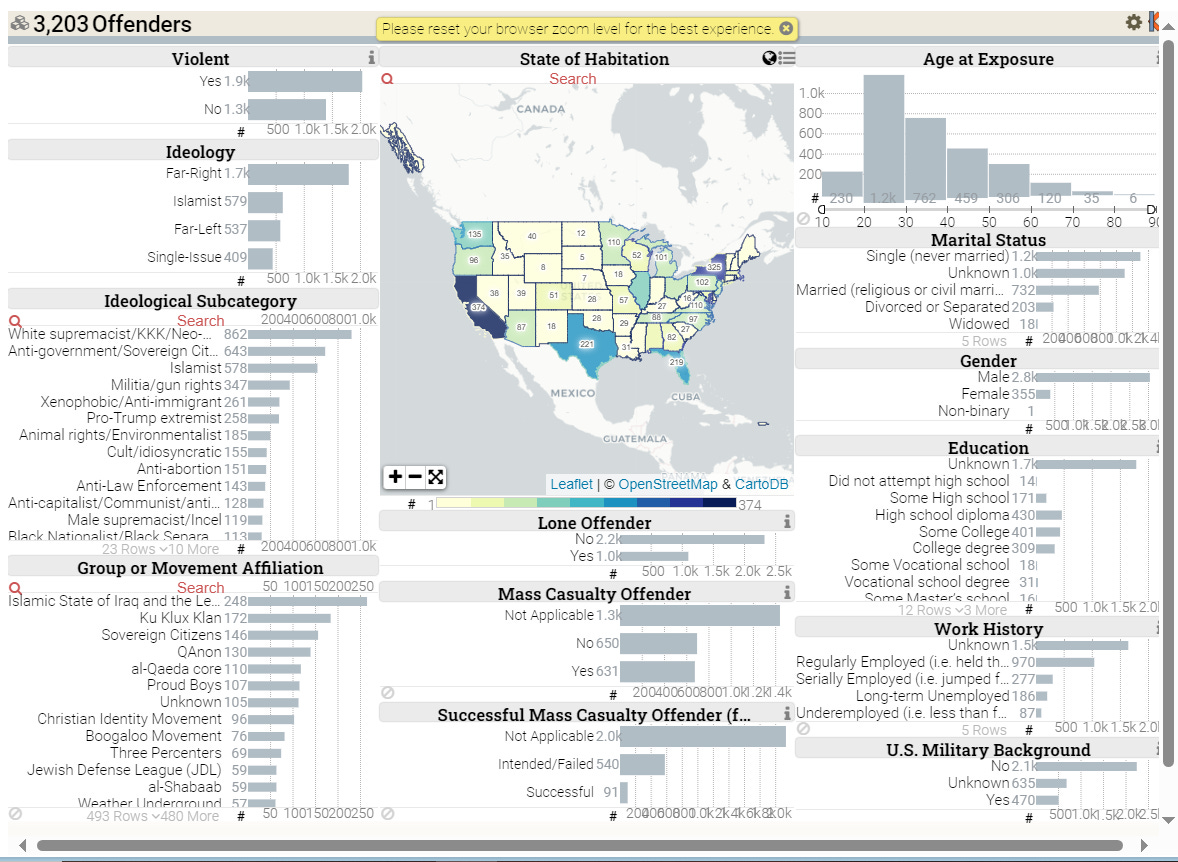

Now as a civilian, I participated in similar efforts related to my specialty, including this particular trip to Germany. Now, seven years later, little has changed in how the US attempts to deal with a very different violent extremist threat, the far-right or generally speaking, MAGA +.

Today’s US far-right, including the entire MAGA movement is both extremism and violent extremism and the most dangerous and lethal form of terrorism to our nation. Yes, there are other forms as well, including on the far-left, but only the far-right has to date, been a threat to our national security and democracy.

Today’s TAT is not about any specific type of extremism but about the only repetitively successful methodology, that I have employed to degrade extremist threats, on and off of the battlefield. It is called Narrative Warfare, which is ridiculously misunderstood by nearly all of the US national security community. Now in our next presidential election cycle, there is an urgent need for DHS and the FBI to shelve failed and failing methodology.

The ongoing onslaught of Narrative Warfare by proponents of a wide variety of extremist movements, especially the most dangerous on the far right demands a serious upgrade in their operations, skills and methods. In short, they must learn how to effectively compete in Narrative Warfare, of which both are devoid of knowledge. Both are obsessed with digital weapons or CYBER and in the FBI’s case, traditional law enforcement activities. This is a grievous error on both of their parts.

Replaying this former article with modernized updates, is an opportunity for not only the two entities with the most responsibility for homeland security, but for other Americans as well This is how that ordinary citizens can also rally to the cause of protecting the nation and our democracy, with their own individual words and actions.

Admittedly, this article is longer and a bit deeper than others, but even so, it is a must learn for all government entities from the Oval Office to a local mayor or county official. I am a firm believer in educating citizens too, when our democracy, safety and unity is at stake. That is why this modernized paper is available to all.

My very best for your week,

Paul

CVE without Narrative

“A book without a story”

By: Paul Cobaugh

Vice President, Narrative Strategies

December 2017/ edited 19 February 2024

Introduction

In the struggle against extremism of all types, the heart and soul of an extremist movement’s campaign, is extremist ideology, delivered in a continually evolving narrative. Narrative is a powerful vehicle for effectively communicating violent and corrupting ideology to potential recruits. Narrative is also what sustains their campaign and especially, psychological control over their adherents. We, the West in particular, have lost the narrative battle against extremism for one simple reason; we have ceded the narrative battlefield to the extremists without a fight. This can and must be corrected or extremism and violent extremism will continue to grow, evolve, and become more dangerous. Tragically, the US and most Western allies have little to no knowledge of what narrative is, how it works and especially, how to win at Narrative Warfare.

- Paul Cobaugh, Vice President at Narrative Strategies

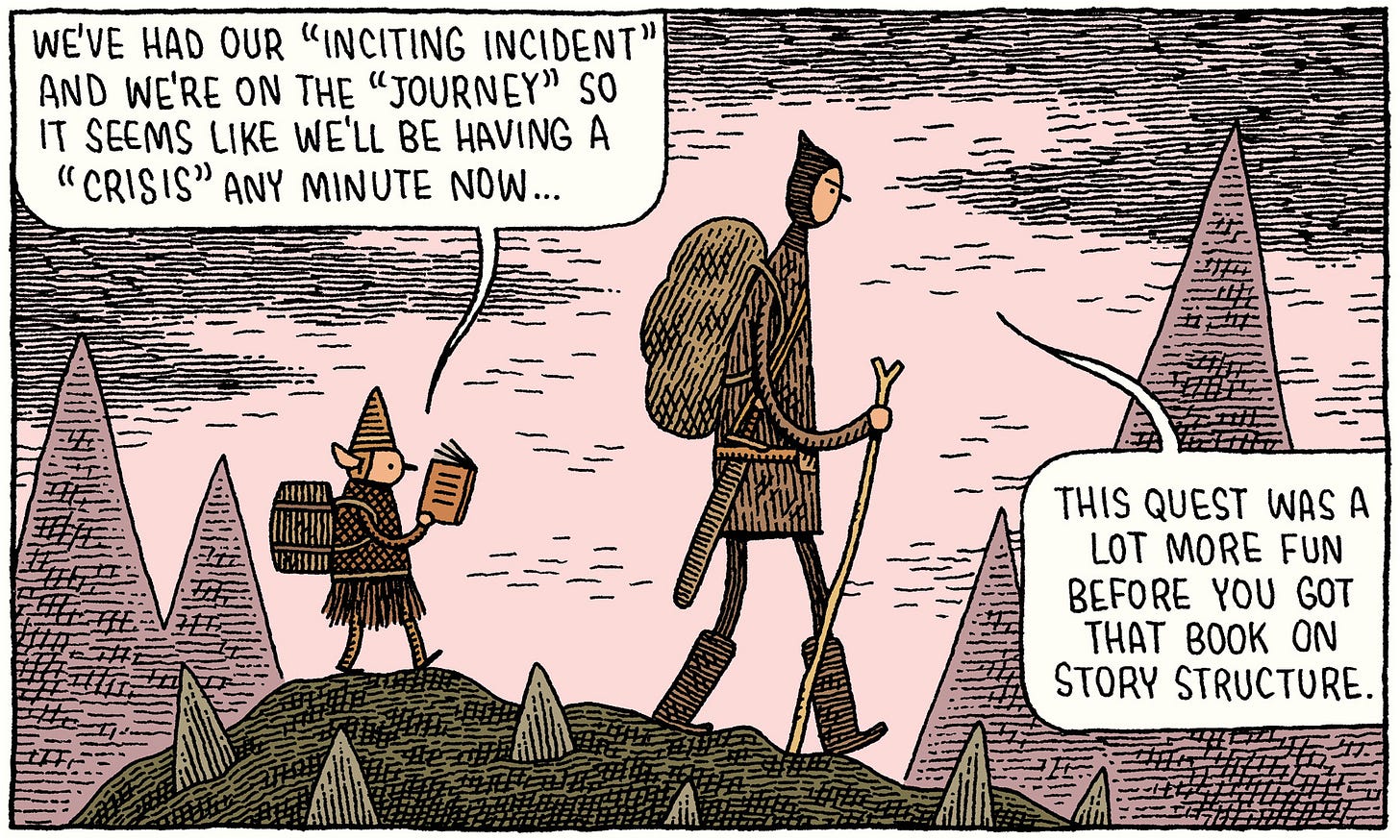

CVE or Countering Violent Extremism, as is now widely agreed upon, is a complex problem with no single cause or cure. Counter-Ideology, community resilience, de-Radicalisation, mitigating trauma; both personal and collective, defeating poverty, identifying, and mitigating disenfranchisement, gang mitigation theories, mental health interventions are simply some but not nearly all the types of programs, that are popular with and being employed by CVE practitioners around the world. All have value in achieving selective results and some more than others. Every one of these programs though share common bonds with related programs. What they do not share is a common narrative that gives meaning to the overall story of countering extremism.

What is needed to unify these programs so that they are mutually reinforcing and overall, more effective, is a narrative strategy that communicates meaning, speaks to the identity, not the demographics of the disparate audiences, and is narrated in the multiple unique forms, most resonant to a wide variety of at-risk audiences.

Addressing a problem as complex as radicalisation and by extension, extremism, requires, as just noted, is a coordinated strategy utilizing multiple mutually reinforcing programs in a carefully choreographed, evolving and sustained campaign. Failing to do so would be like writing a book with disparate and brilliant chapters that have no plot or storyline. Each chapter will teach the reader something potentially valuable but fail to tell the whole story in a meaningful manner and how it relates to the other chapters. Teaching exclusively though, is not “doing.” Doing, requires a wide variety of knowledge and specific tactics that trigger the identity of the audience, in a manner that is predictable and favorable to the overarching strategy.

As our adversaries know full well, narrative is a unique type of story that reinforces identity while giving that identity meaning, therefore a powerful vehicle for triggering identity-based behavior. They may not know academically why and how narrative works, but they know with certainty that it does. This is an especially sharp point when it comes to how Russia supports US far-right/ MAGA narratives.

If we are to collectively write a bestseller about CVE, we must employ the art and science of narrative to give meaning to these brilliant and disparate chapters. The storyline of our book itself, is our narrative, with each chapter supplying a supporting narrative that both reinforces the storyline and gives meaning its own compelling story.

Part I: What is narrative and how does it work?

Narrative, as it applies to CVE or other national security applications, is a term widely quoted but poorly understood. Narrative, when well executed is a delicate and potent combination of both art and science. The intent of this paper is to communicate a basic understanding of narrative as it relates to CVE and to help give CVE practitioners the context for employing not just narrative but an Operational Narrative strategy, as the storyline of their comprehensive approach to countering the scourge of radicalisation and its potential to develop into violent extremism.

What is narrative?

Narrative is as natural to human beings as breathing. We are meaning-seeking animals and our primary means of meaning-making is narrative. Narrative is the way we create, transmit, and in some cases, negotiate meaning. Without narrative, life would be experienced as an unconnected and overwhelming series of random events. We organize, prioritize, and order our experiences through narratives that we both inherent and absorb, with everything we experience during our lifetime. What is more, we understand not only the world around us, but also ourselves, through the narratives we live by; our personal narratives inform our personal identities, our tribal/familial narratives inform our tribal/familial identities, and our national narratives inform our national identity.

“Life stories do not simply reflect personality. They are personality, or more accurately, they are important parts of personality, along with other parts, like dispositional traits, goals, and values,” writes Dan McAdams, a professor of psychology at Northwestern University, along with Erika Manczak, in a chapter for the APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology.

It is critical also to understand that narratives are not truth, even if they are portrayed or understood so. Based on our own NI or Narrative Identity, we all perceive that exact same event or action, from a slightly different perspective. The goal of any narrative is influence. Extremist narratives shape an identity of a recruit to see the world the same as their extremist narrators and ideological narratives. This makes it incredibly difficult to change extremists once they have been thoroughly indoctrinated to the point of acting on those narratives. It is also one of the reasons that fact-checking, while important will not change the mind of someone well radicalized.

An example familiar to most regarding these attributes are the two epic narrative poems of Homer: The Iliad and The Odyssey. Both works are replete with examples of how Homer portrayed the identities of individuals and groups and gave meaning to those identities. These iconic works, still powerful millennia later well demonstrate the durability of identities presented in a well-constructed narrative.

With this baseline understanding of what narrative is, it is crucial to understand its three most basic elements to understand why it is so powerful in the hands of our adversaries as well as a critical vulnerability for those in opposition. Developing this understanding is what will allow us to not only “tell a powerful story” But to employ Operational Narrative as an effective tool of CVE (countering violent extremism).

We, at Narrative Strategies, when introducing the art and science of narrative to operational professionals, focus on what we consider the 4 primary elements of narrative.

1. Identity

2. Meaning, not truth

3. Structure

4. Content

In fact, at Narrative Strategies, we even use a formula comprised of these four elements.

Narrative = M + I + C + S

Before launching into more detail, I try to explain what narrative is to those without a background in the following way:

“We all know family members, spouses, partners, dear friends etc. so well, that we know precisely what to do and say, to make them act in a specific way. For example, what frightens them, what makes them laugh or cry, etc. This is because we know instinctively, what their identity is and what predicably triggers it. This is narrative in its simplest form.”

- Cobaugh

Identity

The whole point of employing a tool such as narrative is that it is powerful communication tool. As any marketing professional knows, “knowing your target audience” is crucial. Without such analysis all marketing of products and ideas would be either ineffective or radically less effective. What most do not realize is that TAA (target audience analysis) is largely demographic and data driven. Demographics and data, while part of identity are both, quite far from the whole of identity. Precision understanding of an audience requires understanding the identity of those targeted, not merely age, race, religion, buying preferences etc.

“Identity: Narratives both transmit identity and co-create identity. For example; a strategic narrative when employed with supporting lesser narratives will trigger the identity layers (as many as possible) of the target audience to create an “us” between the messenger and the TA, or a “them” attached to the opposition.”

- Dr. Ajit Maan, President, Narrative Strategies

In order to predictably influence a group, any communication strategy with narrative as its core must connect with the identity, not just the demographics of that particular group. This then prompts the question, “what is the difference between conventional target audience analysis and TAA that incorporates identity into that analysis?”

Understanding the identity of an individual group requires analysis, or what we term CIA (Cultural Identity Analysis) The difference between TAA and CIA can be confusing so let’s look at an example which should be of value in explaining the difference.

During consecutive deployments to Afghanistan, 2009-2013 I learned to put narrative at the core of my Information Operations campaigns. In order to achieve results in the East where Pashtun tribes dominate the cultural landscape it was incumbent upon me to learn “who rural Pashtuns are”. Pashtun Tribes, largely (but not exclusively) inhabiting much of Afghanistan and Pakistan express their identity through a millennia old tribal honor code called Pashtunwali. Pashtunwali not only prescribes behavior but that behavior defines who Pashtuns are individually and collectively. Pashtun history, traditions, governance are literally built upon and representative of some aspect of Pashtunwali.

When dealing with Pashtuns success depends in large part on how your words and actions are interpreted by way of Pashtunwali. This tribal honor code has developed over millennia and predates Islam. Although most Pashtuns consider Pashtunwali to be synonymous with Islam, it is not. This is representative of how the narrative of Pashtunwali gives meaning to Pashtun identity despite truth.

Pashtunwali regulates virtually every aspect of a rural Pashtun’s life and no thought or action is devoid of considering the ramifications of honor inherent to the code. This concept represents how the narrative of Pashtunwali triggers behavior. This is one reason that violent Islamic extremist groups espousing Sharia law, struggle to build sustainable relationships with Pashtun insurgents. The Taliban, largely Pashtun are often and violently at odds with non-Pashtun extremists attempting to impose an aberrant version of Sharia common among Sunni oriented violent extremists.

Extremist narratives rarely resonate with rural Pashtuns unless presented by a respected and traditional tribal elder and are presented in story form and couched with tenets of Pashtunwali. Most Pashtun elders though would refuse to act with or comply to the extremist narratives of AQ or later, ISIKP etc. This is why extremists marginalized tribal elders and elevated the traditionally lowly mullahs to higher status, in order to better control indigenous populations.

During my learning period regarding rural Pashtuns, if I had only considered demographics such as age, rural vs. city dwelling, married, number of children, household income, religion, or profession, I would have learned a little of value regarding what triggers behavior in rural Pashtuns. The bottom line is that identity, not demographics matter most.

Meaning, not truth

Meaning: Narratives do not necessarily tell the truth, they give meaning to a succession of events, facts (real or otherwise). That does not imply that narratives involve lies. It does though mean that when narrative is presented correctly it does not allow the audience to derive their own meaning. A successful narrator (s) control this.

Once again returning to our comparison to Homer’s works, we see clearly that these powerful narratives solidified the identity of the those in the story and gave meaning to the events of the story. Neither The Iliad nor The Odyssey are considered purely factual accounts but occasionally and partially historical accounts of events replete with meaning regarding Greek Gods, their attributes, human frailties etc. Attributed to the 8th century B.C. both narratives are still are part and parcel of Greek identity. Both also still offer meaning regarding the human experience in historical context. For nearly two millennia schoolchildren and well-educated adults alike can recount the meaning of these extraordinary narratives to include having a relative understanding of what it meant to be an ancient Greek.

“Once certain stories get embedded into the culture, they become master narratives—blueprints for people to follow when structuring their own stories, for better or worse.”

- Monisha Pasupathi, a professor of developmental psychology at the University of Utah

As an American and a Texan, the story of the Alamo is another very good example of meaning, not facts as expressed through narrative. Presented from the American side, the fight at the Alamo for Texan independence from Mexico, was a soul-stirring story recounting the meaning of fighting for freedom against an oppressive government. The 1960s movie starring John Wayne is the narrative that most Americans identify with although historical analysis reveals many glaring discrepancies with the movie. The same story told from the Mexican perspective was one of a courageous Army marching several thousand kilometers to put down a rebellion of disrespectful and ungracious insurgents. Both versions of the same story and with common facts give divergent meanings to the identities of both American and Mexican audiences. Such is the power of a persuasive narrative.

What is important in this portion of this paper is that when developing a narrative, it important to develop the meaning of your story based on the identity of the audience intended.

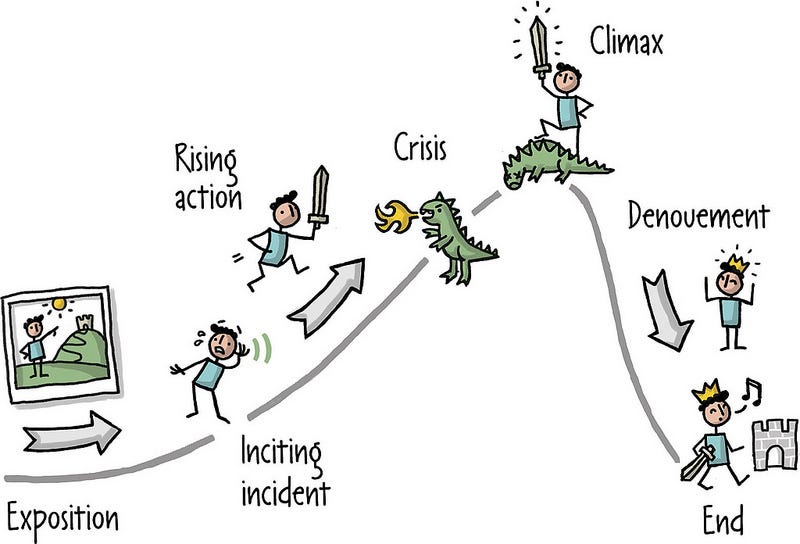

Structure

Form/Content: When most of us think of a narrative we think about what the narrative is about – the theme or the content. Equally important though is structure or form. What the story is about is content and how the story is told, the structure. Both form and structure are culturally dependent.

Western stories follow a different path than non-western. For example, a western styled narrative will generally be relatively linear with a beginning, middle (conflict) and end or resolution. This is not necessarily the form non-western literature takes. It is fairly common outside the west for story-telling to take a meandering path as well as be epic in nature. Meaning and multiple conflicts or evolutions will occur throughout the telling with characters displaying identity traits common among the elements of society most likely to hear, read or watch the story. Also common will be that the challenges or conflict encountered will be those most common to the intended audience. This allows the narrator to express meaning in how those challenges are met, resolved (or not) and all within the framework of identities common among intended audiences.

A related topic to form and one most especially relevant to CVE and political narrators is length and presentation. One of the most challenging aspects of fighting extremism is social media and the requirement to condense meaning, identity and structure into a short social media post, tweet, or article. This accentuates the problem of “getting a narrative right” for a specific target audience. Brevity for some of the most important audiences requiring mitigation and relative to radicalisation, makes is acutely important to make every letter, punctuation mark, meme, or associated music count. This is simply another reason that cultural identity analysis is of the utmost importance.

Part II: Putting it all together

By now I would imagine that everyone is wondering what all this talk of Homer, the Alamo, Pashtuns etc. has to do with narrative centric CVE. The answer is simply that, effective CVE requires many different approaches and in order to communicate effectively, a narrative strategy is required. Each approach or program targets multiple unique audiences. Therefore, the overall campaign requires a compelling narrative while each supporting program would also require its own narrative, tied to the master narrative. These individual narratives, when part of an overall campaign would be considered “interactive narratives”, or sub-narratives.

The preceding sections are the most basic building blocks of narrative. Like any artisan, how one arranges these blocks when building a comprehensive program is dependent upon the skill, artistic vision, and expertise of the artist. This is why we often say “the art and science” of narrative. The blocks are based on science and how they are arranged would be the art.

At the very beginning, were listed several examples of different types of CVE programs. Every one of them is based on research and every one of them have demonstrated some level of contribution to the mitigation of radicalisation when executed properly. What is rarely seen is multiple approaches or programs interactively coordinated with each other. This we would contend is a major flaw in most CVE campaigns.

There is no reasonable debate as to the complexity of the problem of CVE, its causes, and its potential treatments. If we can accept this premise, then we must also accept that we must carefully and expertly coordinate the application of multiple approaches at the same time. In order to do this, there is the absolute requirement to be able to communicate and demonstrate effectively, in a manner that expresses our meaning to the identities of those we are attempting to reach and, in a manner, most resonant to them. Based on this statement, it is essential that narrative, based on its foundational elements become the “glue” that binds common but disparate objectives together. Our adversaries, be they right-wing extremists or violent Jihadist types do this inherently. As an example, DAESH, AQ, Boko Haram all share common overarching narratives and yet each have their own unique narrative which triggers behavior in their own sphere of influence.

It is not enough to merely state that terrorism based on extremist ideology is bad and that we must stand against it. The individuals reading this are all too aware that this statement is grotesquely oversimplified. Our extremist adversaries understand the need for a compelling and motivational narrative. Our adversaries by all measure have succeeded at some level of employing narrative to support their goals. To think we in opposition, can effectively mitigate extremism without competing effectively in the narrative space, defies logic, science and experience.

This does mean merely employing “counter-narratives.” Our enemies have employed what is best described as “weaponized narrative.” We would submit that in order to compete on the narrative battlefield, we need to employ what we consider to be Operational Narrative. Operational narrative is a strategy that combines both a compelling narrative along with supporting interactive narratives that does not allow our adversaries to dominate the narrative space. Narratives, counter-narratives along with supporting interactive narratives must be deployed in conjunction with each other and well-orchestrated in order to trigger the identities targeted in a predictable and favorable manner.

This is a challenging task and not to be undertaken lightly. To be effective, there must be a coordinating authority that can assist in developing content, provide cultural identity analysis, coordinate communications and actions, and provide the assessments so critical to “fine-tuning” and adjusting content throughout the campaign.

Making narrative operational requires intelligence specifically designed to support this effort. Conventional intelligence operations do not currently nor routinely collect and analyze narratives. Additionally, current intelligence operations do not collect and do cultural identity analysis of the human terrain. These are glaring gaps in our capability to employ Operational Narrative. These gaps though can be closed and with far less difficulty than it would be imagined. It is a matter of refocusing already existing resources and training collectors and analysts to filter information in accordance with the three foundational elements of narrative.

Once armed with cultural identity analysis of multiple at-risk groups and analysis of our adversaries’ narrative, it is possible to build narratives and related supporting narratives that effectively compete for dominance in the narrative space as well as build the interactive narratives that both support multiple programs and effectively counter adversarial narratives. Whether a program targets migrants, traumatized communities, or economic hardship they are all part of an overarching campaign but playing a specialized role.

The most basic and admittedly simplified Operational Narrative paradigm would be comprised of the following;

1. A simple but compelling over-arching narrative that is comprised of general but resonant themes.

2. Every program targeting extremism under the umbrella of the over-arching program would also need their own interactive narrative that relates to the over-arching though focused on the identity, meaning and form most resonant with their specific audience

3. Narrators selected based on cultural identity analysis

4. Access to and resources required to disseminate narratives and supporting themes and messages both long term and in real time

5. Cultural analysts for both development and assessment of campaigns

6. A campaign control structure capable of coordinating messaging with observables

There is no doubt that coordinating this effort is a seemingly daunting task. It will require a concentrated effort by a variety of professional communities and programs, applying all manner of rigor to developing the strategy as well as acquiring government support. These tasks though are not insurmountable. I have done this on and off of battlefields, with minimal support. We are unfortunately living in a time when extremism is not waning. In fact, opposing types of extremism are driving each other into more violence. This is commonly seen in the symbiotic relationship between violent extremism based on an aberrant from of Islam and the extremism of the far right. If we choose to continue the path we are on and not develop new and more effective mitigation, it is at our own peril.

Conclusion

This paper began by comparing a comprehensive approach to CVE as a book of brilliant chapters but devoid of a storyline. As has been presented, an Operational Narrative campaign, built around the three primary elements of; identity, meaning not truth and structure offers the real possibility of correcting this strategic oversight. Any battle uncontested cannot be won. Narrative is the primary weapon of our extremist adversaries. We can ill afford to continue allowing them to wield it unopposed. This falls into the category of “not bringing a knife to a gun fight.”

The hard truth though and one that must be addressed by nations, regions, NGOs or otherwise is that in order to employ Operational Narrative, all participating entities must be willing to work together in a well-coordinated and effective manner. This is one of the most daunting hurdles to overcome. All the elements of a comprehensive campaign have invaluable expertise and honorable intent but that simply is not enough. Like the book in our analogy, each entity, like characters in a narrative has a unique and specific role to play in order for a campaign to be a “best-seller”. Everyone must accept their role and direction for a comprehensive campaign to achieve its potential.

We will close on a note of optimism. During our collective careers, the Narrative Strategies team has encountered countless brilliant, selfless, and dedicated professionals. There is not the slightest doubt that those we’ve encountered throughout, understand the concepts and potential of Operational Narrative. Our biggest challenge and one which can be rectified through the advocacy of CVE professionals, is to convince those in policy that we must engage on the narrative field of battle, in a convincing manner and sooner than later. We have every confidence that should we in the narrative field and the remarkable CVE professionals recognizing the critical value of a narrative-centric campaign come together, we will succeed in changing policy and operations for the good all.

The final words for this paper will be a kind and grateful “thank you” to Dr. Ajit Maan, mentor, scholar, and friend. She, as always has been gracious in supporting this paper with her time and expertise to ensure that the most accurate and useful knowledge was contributed. In the end, we all have benefited.

Paul Cobaugh, Vice President of Narrative Strategies, prior to retirement from the US Army in 2015 spent the past decade supporting the US Special Operations Command focused on CT and CVE. He has authored;

Modern Day Minutemen or how to protect the 2020 Election

and has co-authored;

Soft Power on Hard Problems: Strategic Influence in Irregular Warfare

Narrative Warfare, Primer, and Study Guide,

and co-edited Information Warfare, the lost tradecraft by Dr. Howard Gambrill Clark

Works Cited

Cobaugh, C.-a. P. (2017). Soft Power on Hard Problems. Hamilton Publishing.

Erika Manczak, i. a. (2015, August). Life's Stories. Retrieved from The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/08/life-stories-narrative-psychology-redemption-mental-health/400796/

Maan, D. A. (2015). Professor/ Author Counter-Terrorism Narrative Strategies . University Press.

McAdams. (2015, August). Life's Stories. Retrieved from The Atlantic : https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/08/life-stories-narrative-psychology-redemption-mental-health/400796/

Monisha Pasupathi, a. p. (2015, August). Professor of developmental psychology at the University of Utah. The Atlantic.

.